Often, we’re guilty of paying more attention to the ‘what’, when we should be focusing on the ‘why’.

This week, we’re taking a look at five psychological tricks that the mind plays, and explaining how a great user onboarding flow takes advantage of each one.

As always, if you have questions or comments, hit us up @nickelledapp on Twitter, or in the comments section below.

1) Need For Cognitive Closure

In 1927, long before the idea of “closure” had been coined as a concept, German-American psychology professor Kurt Lewin noticed that his waiter appeared to have odd memory quirks when dealing with orders.

Presented with unpaid orders, the waiter was able to recall information with ease, but as soon as the bill had been paid, he was unable to remember any more details of the orders.

His student, Bluma Zeigarnik, began a series of experiments to try to replicate the effect under laboratory conditions, and in 1927, wrote her first paper that offered some explanation as to what was happening.

Zeigarnik challenged 164 subjects to complete a series of simple tasks and challenges, such as stringing beads or making clay figures. Half of the group were allowed to complete the tasks, the other half were interrupted part way through.

When Zeigarnik asked participants which tasks they could recall, they were twice as likely to remember the tasks they had not completed.

The study, known as “On Finished and Unfinished Tasks” and translated into English here, kicked off the study of the complex relationships humans have with completion, which continues to this day.

In the subsequent decades, we have learned much about closure to explain the behaviour exhibited by Lewin’s waiter — fundamentally, we’re motivated to avoid open, ambiguous scenarios by resolving the situation as quickly as possible (the “urgency tendency”) and maintaining that state for as long as possible (the “permanence tendency”).

In general, this trait is a good thing — it allows us to stay true to our goals, to complete unfinished business and to get to the end of our to-do lists, for instance. However, in some cases, our need for cognitive closure can lead to a “completion bias”, where we sacrifice harder, important goals in exchange for the psychological satisfaction of completing, smaller, easier ones.

It may also reduce our willingness to absorb fresh information when we believe that closure has been achieved — a phenomenon coined by Arie Kruglanski as “Seizing and Freezing”.

In onboarding, therefore, the need for cognitive closure can be leveraged to induce new customers to complete important tasks by leaving them open, while at the same time ensuring that the user remains willing and able to change perspective when new information is offered.

A checklist, for example, plays on our need for cognitive closure — presented with a list of tasks, many of us will feel the need to get them completed.

A good onboarding experience will ensure that the checklist contains all of the critical actions required to bring a user to their “Aha Moment”, where the value of the product is immediately clear.

Alongside a checklist, there are other ways to trigger our need for cognitive closure — email requests, app badges and in-app messaging can all be used to send messages reminding us that the process which the user entered into when they began using the product is not yet complete.

What to try

- Offer an easily-accessible onboarding “checklist” which users can complete at their own pace

- Be clear about expectations before and during onboarding to avoid users ‘seizing and freezing’ on a process or state that hasn’t yet been completed

2) The endowed progress effect

If you collect loyalty cards from retailers that feature “stamps” — the type where a certain number of stamps earn you a free gift, for example — you’ve seen the endowed progress effect in action.

Think back to the last time you were offered a card like this, and try to recall whether it had any completed stamps. If so, that’s likely down to the work of Joseph Nunes and Xavier Dreze, two psychologists who started investigating endowed progress in 2006.

In a study that contributed a huge amount to our understanding of consumer behavior, Nunes and Dreze set up a system offered to 300 patrons of a car wash, where eight stamps were required for a free car wash.

In their experiment, the researchers split the 300 customers into two groups and gave the members of each group a different type of loyalty card. In one set, the loyalty card had eight boxes to complete, and in the other, there were eight boxes to complete but two already completed, for a total of ten boxes.

Although the purchase requirements from this point were exactly the same, Nunes and Dreze found that the redemption rate of the cards that had been ‘endowed’ with the extra two stamps was 34%, far higher than the 19% of cards with only eight stamps. In addition, customers with ‘endowed’ cards came back more frequently, completing their cards faster than those with the non-endowed cards.

The study, available online here, is now widely used as the basis for loyalty card programs, with the practice of a free first or second stamp commonplace among retailers.

Nunes and Dreze were able to quantify what many of us intrinsically feel — that perception plays a huge role in our motivation, and when we perceive ourselves to be closer to a goal, we’re more likely to push ourselves to reach it.

As a psychological trick, endowed progress is hugely valuable, because it suggests that we can prompt others into completing tasks by suggesting that they are closer to completion than they really are.

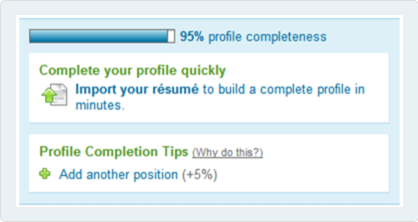

In onboarding, progress is generally showed as the completion of a list (as above) or on some form of progress chart such as the below example from LinkedIn:

Thanks to Nunes and Dreze, we know that our new users shouldn’t start at zero, however — they’re far more likely to complete all steps if they feel they’re close to the end.

By implication, we also increase motivation every time a user makes some progress — suggesting that easier steps should be placed at the beginning of an onboarding program, and harder ones at the end, where the goal is in sight and easier to visualize.

What to try

- Don’t start progress bars at zero – start them at 20% or so to create the illusion that progress has already been made

- Put the easiest steps at the beginning and the hardest ones at the end of your onboarding program

- Experiment with adding artificial endowment to areas that require a high-level of user effort (long forms, for example)

3) Hyperbolic Discounting

Globally, we are facing a pensions crisis. According to Chicago Booth, 53 percent of workers in the United States are at risk of having inadequate funds to maintain their lifestyle through retirement, and the situation is not dissimilar in the United Kingdom.

One of the reasons pension contributions have fallen so significantly has been the growth of optional workplace-based pensions, now commonplace in developed countries. In theory, the idea works well — employer matching makes joining a no-brainer for employees, and it’s the most effective way for the burgeoning Western middle class to save. However — there’s a major snag — almost a quarter of us fail to register at all.

Passing up the chance of “free” money in the form of a pension scheme may seem crazy, but there’s a well-understood psychological phenomenon behind it, known as hyperbolic discounting.

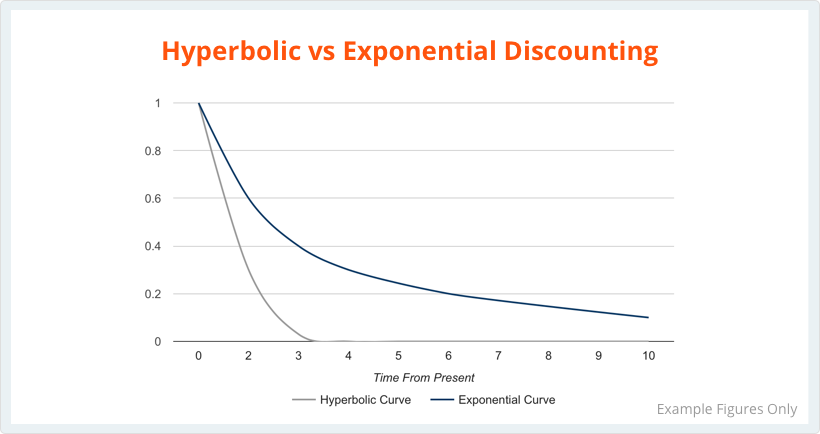

Hyperbolic discounting can be best explained with the aid of a simple choice — given the option between receiving $50 today or $100 a year from now, most people will choose to take the $50 immediately.

There’s no rational explanation for this decision (assuming the individual isn’t desperate for money) — financially, it makes far more sense to take twice the amount of cash, even if it comes further down the line. But most people don’t.

The phenomenon occurs because we discount the value of the $100 in our head, reducing its value by the time we have to wait to get it.

It’s known as hyperbolic discounting because of what happens when people are given the choice between $50 in five years or $100 in six years — despite having to wait exactly the same amount of time for their money to double, most will choose $100 given the five-year distance ahead. This behavior, when plotted on a graph, makes a hyperbolic curve, rather than an exponential curve, which would produce a consistent reduction in choice over time:

Hyperbolic discounting is why we don’t pay into our pensions, even when there are overwhelming economic arguments to do so. Given the choice between $300 in our pockets and $300 saved for the future, we’ll take the immediate $300 and ignore the fact that $300 invested at an early age can produce huge dividends over time thanks to compound interest.

If you start looking, you’ll see hyperbolic discounting in use by marketers almost everywhere. Buy-now, pay-later schemes and credit cards are two of the most common applications which prey on our weakness for the present, but other tricks such as free gifts and inflated short-term pricing are also used to trick us into forgoing a good deal in the future for a poor one right now.

During onboarding, there are some neat opportunities to use this mindset to our advantage.

First of all, hyperbolic discounting suggests that we can induce certain actions among users through the means of short-term rewards — even if we know that the long-term reward (the successful use of a product or service) may be some way off.

Given that a user is far more likely to opt for with a short-term outcome than they are for a long-term one, consider using short-term rewards to trigger behaviors that are beneficial over the long-term.

Secondly, SaaS businesses may also consider raising their prices, while simultaneously deferring payment. If you offer a 14-day onboarding period, it may be worth experimenting with offering 30 days with a higher monthly subscription rate, given we know how users mentally discount prices with time in their heads.

What to try:

- Offer short-term rewards in your onboarding to nudge long-term desired behaviors

- Consider experimenting with the price/trial length combination

4) The Ambiguity Effect

Back when we were primitive creatures, the unknown was to be feared. Given the choice between a red berry and a black berry and knowing that either berry might (or might not) kill it, an intelligent creature will pick the option it knows the most about. If it ate a black berry two days ago and is still alive, or saw a friend eat a black berry and live, most would choose the black berry, even though the red berry may not be poisonous either.

This bias towards knowledge is known as the ambiguity effect, and it has many implications for how we live our lives. When Google Maps suggests a route that’s different from the one that we know and love, we may choose to ignore the advice, even though it’s faster. When an investor eschews stock picks in favor of safe investments such as bonds, he or she is moving away from the unknown. Both of these examples are driven by our instinct to avoid ambiguity.

The effect is most conclusively proven by an experiment in which participants are asked to pick balls from a bucket containing 30 red, black or white balls.

If the participants are told that there are 10 red balls and an indeterminate number of black and white balls, and then asked whether they want a prize for picking a red or a black ball, the majority will opt to choose the prize that rewards them for choosing a red ball.

Choosing red, we know, offers a 1/3 possibility of a win. However, choosing black has the same chance, as there are an indeterminate number of black balls in the black and white mix — there could be 20 black balls, there could be zero, so the probability evens out to ten. Given the certainty of a 1/3 possibility, however, most humans choose red, avoiding the ambiguity that comes with the other choice.

The ambiguity effect has a significant effect on many of the choices we make in day-to-day life — it implies that some of the time, we may be making the wrong choice because we are afraid of the unknown.

In onboarding, it suggests that a user will opt for known quantities over unknown quantities and if we want to lead users down a certain path, we need to make sure that they’re furnished with as much information as possible before we ask them to make a decision.

So in the case where a customer needs to invite their colleagues to use an app, we should offer as much data as possible on how we’ll be using the email address that is provided. If we offer links to external websites, we should offer previews of what the user can expect when they get there. And in the case where success is dependent on an in-person pitch or customer success call, we should be putting the user’s mind at ease about exactly what that meeting will entail so that there are no niggling doubts about whether to take the meeting or not.

What to try

- Be absolutely clear about the ‘why’ for every step of your user onboarding process

- Reduce third-party pages or navigation outside of the app as much as possible

5) Choice-supportive bias

Hopefully the psychological tricks above have given you some ideas of how to make your onboarding process better for your users.

I’ll end with a bias which often drives actions in customer success teams — it's known as the choice-supportive bias.

As humans, we’re inherently happier with the choices we make compared to those we don’t, even if all available evidence suggests that we may have made the wrong decision. When we choose between options A and B and select option A, we’re likely to subsequently downplay the faults of A over B, as well as amplifying the advantages of A.

In other words, our memory distorts our recollection of a decision — it can also, for instance, insert positive aspects of a chosen option, even if they weren’t originally presented as part of the decision.

Deciding to sign up and get started with a new SaaS app is a big decision — to get as far as an onboarding process, it’s likely that a new customer has already weighed multiple options and decided against others to choose one specific solution.

The choice-supportive bias tells us that our brains desperately want the decision to work out — we’re looking for evidence that we made the right choice, and we’re looking to avoid the cognitive dissonance that arises from the idea that we made the wrong choice.

This suggests that every part of an onboarding flow should be designed to increase confidence that the right decision has been made. Increase the simplicity, remove unnecessary steps, surprise and delight the user and use the psychological tricks above to remove any doubt that the user has chosen correctly when they picked your app.

Your customers desperately want to succeed with your product, even if they don’t know it themselves. Are you allowing them to do that?